This is the first in a series of posts I’ll be writing on the work we’ve been

doing to improve the stability of Mono’s

log profiler. All improvements

detailed in these blog posts are included in Mono 4.6.0, featuring version 1.0

of the profiler. Refer to the

release notes for the full list of changes

and fixes.

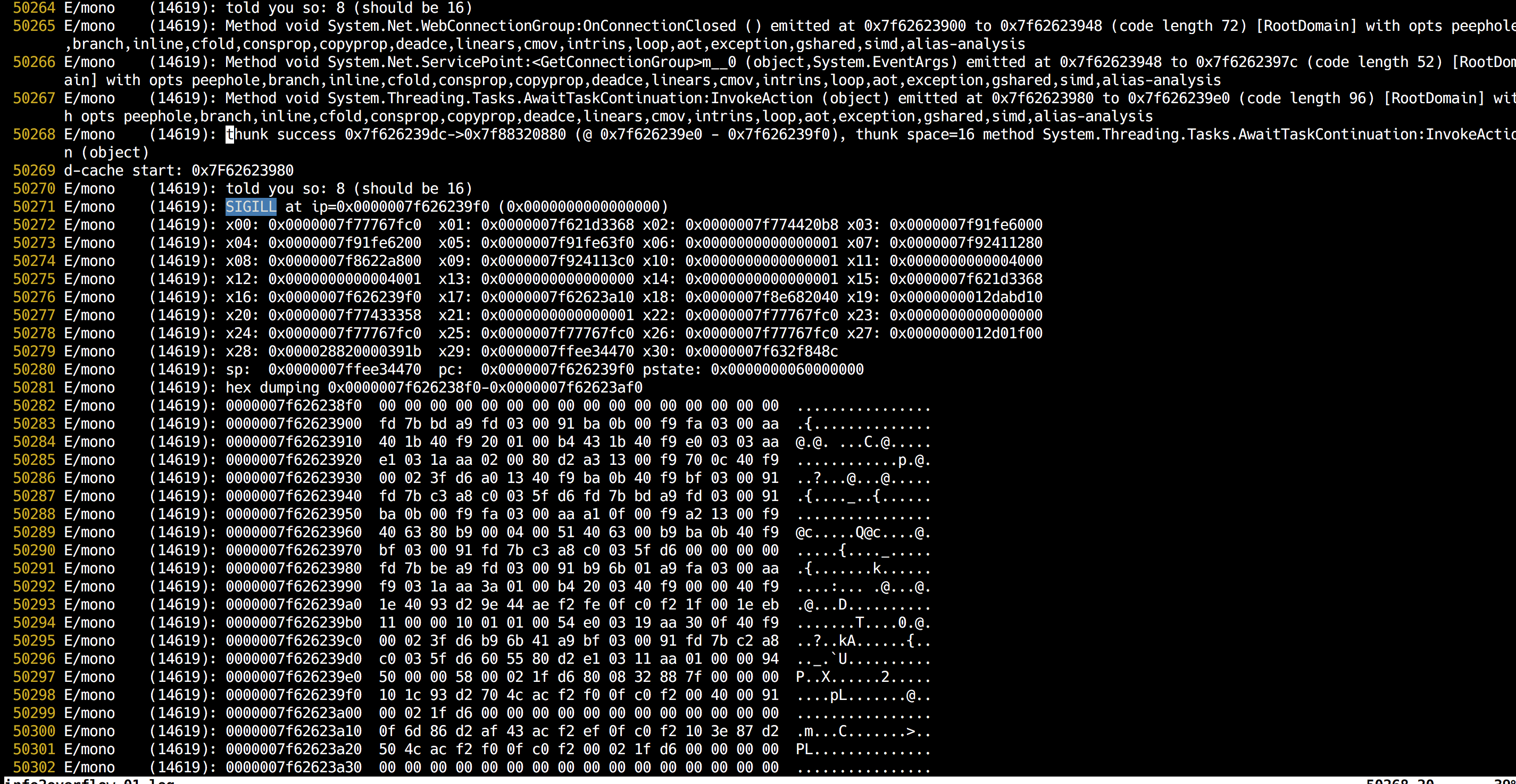

The problem we’ll be looking at today is a crash that arose when running the

profiler in sampling mode (i.e. mono --profile=log:sample foo.exe) together

with the SGen garbage collector.

The Problem

SGen uses so-called managed allocators to perform very fast allocations from

the nursery (generation 0). These managed allocators are generated by the Mono

runtime and contain specialized code for allocating particular kinds of

types (small objects, strings, arrays, etc). One important invariant that

managed allocators rely on is that a garbage collection absolutely cannot

proceed if any suspended thread was executing a managed allocator at the time

it was suspended. This allows the managed allocators to do their thing without

taking the global GC lock, which is a huge performance win for multithreaded

programs. Should this invariant be broken, however, the state of the managed

heap is essentially undefined and all sorts of bad things will happen when the

GC proceeds to doing scanning and sweeping.

Unfortunately, the way that sampling works caused this invariant to be broken.

When the profiler is running in sampling mode, it periodically sends out a

signal (e.g. SIGPROF) whose signal handler will collect a managed stack trace

for the target thread and write it as an event to the log file. There’s nothing

actually wrong with this. However, the way that SGen checks whether a thread is

currently executing a managed allocator is as follows (simplified a bit from

the actual source code):

static gboolean

is_ip_in_managed_allocator (MonoDomain *domain, gpointer ip)

{

/*

* ip is the instruction pointer of the thread, as obtained by the STW

* machinery when it temporarily suspends the thread.

*/

MonoJitInfo *ji = mono_jit_info_table_find_internal (domain, ip, FALSE, FALSE);

if (!ji)

return FALSE;

MonoMethod *m = mono_jit_info_get_method (ji);

return sgen_is_managed_allocator (m);

}

To understand why this code is problematic, we must first take a look at how

signal delivery works on POSIX systems. By default, a signal can be delivered

while another signal is still being handled. For example, if your program has

two separate signal handlers for SIGUSR1 and SIGUSR2, both of which simply

do while (1); to spin forever, and you send SIGUSR1 followed by SIGUSR2

to your program, you’ll see a stack trace looking something like this:

(gdb) bt

#0 0x0000000000400564 in sigusr2_signal_handler ()

#1 <signal handler called>

#2 0x0000000000400553 in sigusr1_signal_handler ()

#3 <signal handler called>

#4 0x00000000004005d3 in main ()

Unsurprisingly, if we print the instruction pointer, we’ll find that it’s

pointing into the most recently called signal handler:

(gdb) p $pc

$1 = (void (*)()) 0x400564 <sigusr2_signal_handler+15>

This matters because SGen uses a signal of its own to suspend threads in its

STW machinery. So that means we have two signals in play: The sampling signal

used by the profiler, and the suspend signal used by SGen. Both signals can

arrive at any point, including while the other is being handled. In an

allocation-heavy program, we could very easily see a stack looking something

like this:

#0 suspend_signal_handler ()

#1 <signal handler called>

#2 profiler_signal_handler ()

#3 <signal handler called>

#4 AllocSmall ()

...

(Here, AllocSmall is the managed allocator.)

Under normal (non-profiling) circumstances, it would look like this:

#0 suspend_signal_handler ()

#1 <signal handler called>

#2 AllocSmall ()

...

Mono installs signal handlers using the sigaction function with the

SA_SIGINFO flag. This means that the signal handler will receive a bunch of

information in its second and third arguments. One piece of that information

is the instruction pointer of the thread before the signal handler was invoked.

This is the instruction pointer that is passed to the

is_ip_in_managed_allocator function. So when we’re profiling, we pass an

instruction pointer that points into the middle of profiler_signal_handler,

while in the normal case, we pass an instruction pointer that points into

AllocSmall as expected.

So now the problem is clear: In the normal case, SGen detects that the thread

is executing a managed allocator, and therefore waits for it to finish

executing before truly suspending the thread. But in the profiling case, SGen

thinks that the thread is just executing any arbitrary, unimportant code that

it can go right ahead and suspend, even though we know for a fact (from

inspecting the stack in GDB) that it is actually in the middle of executing a

managed allocator.

When this situation arises, SGen will go right ahead and perform a full

garbage collection, even though it’ll see an inconsistent managed heap as a

result of the managed allocator being in the middle of modifying the

heap. Entire books could be written about the incorrect behavior that could

result from this under different circumstances, but long story short, your

program would crash in random ways.

Potential Solutions

At first glance, this didn’t seem like a hard problem to solve. My initial

thought was to set up the signal handler for SIGPROF in such a way that the

GC suspend signal would be blocked while the handler is executing. Thing is,

this would’ve actually fixed the problem, but not in a general way. After all,

who’s to say that some other signal couldn’t come along and trigger this

problem? For example, a programmer might P/Invoke some native code that sets up

a signal handler for some arbitrary purpose. The user would then want to send

that signal to the Mono process and not have things break left and right. We

can’t reasonably ask every Mono user to block the GC suspend signal in any

signal handlers they might set up, directly or indirectly. Even if we could, it

isn’t a good idea, as we really want the GC suspend signal to arrive in a

timely fashion so that the STW process doesn’t take too long (resulting in long

pause times).

OK, so that idea wasn’t really gonna work. Another idea that we considered was

to unwind the stack of the suspended thread to see if any stack frame matches a

managed allocator. This would solve the problem and would work for any kind of

signal that might arrive before a GC suspend signal. Unfortunately, unwinding

the stack of a suspended thread is not particularly easy, and it can’t be done

in a portable way at all. Also, stack unwinding is not exactly a cheap affair,

and the last thing we want is to make the STW machinery slower - nobody wants

longer pause times.

Finally, there was the nuclear option: Disable managed allocators completely

when running the profiler in sampling mode. Sure, it would make this problem go

away, but as with the first idea, SGen would still be susceptible to this

problem with other kinds of signals when running normally. More importantly,

this would result in misleading profiles since the program would spend more

time in the native SGen allocation functions than it would have in the

managed allocators when not profiling.

None of the above are really viable solutions.

The Fix

Conveniently, SGen has this feature called critical regions. They’re not quite

what you might think - they have nothing to do with mutexes. Let’s take a look

at how SGen allocates a System.String in the native allocation functions:

MonoString *

mono_gc_alloc_string (MonoVTable *vtable, size_t size, gint32 len)

{

TLAB_ACCESS_INIT;

ENTER_CRITICAL_REGION;

MonoString *str = sgen_try_alloc_obj_nolock (vtable, size);

if (str)

str->length = len;

EXIT_CRITICAL_REGION;

if (!str) {

LOCK_GC;

str = sgen_alloc_obj_nolock (vtable, size);

if (str)

str->length = len;

UNLOCK_GC;

}

return str;

}

The actual allocation logic (in sgen_try_alloc_obj_nolock and

sgen_alloc_obj_nolock) is unimportant. The important bits are

TLAB_ACCESS_INIT, ENTER_CRITICAL_REGION, and EXIT_CRITICAL_REGION. These

macros are defined as follows:

#define TLAB_ACCESS_INIT SgenThreadInfo *__thread_info__ = mono_native_tls_get_value (thread_info_key)

#define IN_CRITICAL_REGION (__thread_info__->client_info.in_critical_region)

#define ENTER_CRITICAL_REGION do { mono_atomic_store_acquire (&IN_CRITICAL_REGION, 1); } while (0)

#define EXIT_CRITICAL_REGION do { mono_atomic_store_release (&IN_CRITICAL_REGION, 0); } while (0)

As you can see, they simply set a variable on the current thread for the

duration of the attempted allocation. If this variable is set, the STW

machinery will refrain from suspending the thread in much the same way as it

would when checking the thread’s instruction pointer against the code ranges of

the managed allocators.

So the fix to this whole problem is actually very simple: We just set up a

critical region in the managed allocator, just like we do in the native SGen

functions. That is, we wrap all the code we emit in the managed allocator like

so:

static MonoMethod *

create_allocator (int atype, ManagedAllocatorVariant variant)

{

// ... snip ...

MonoMethodBuilder *mb = mono_mb_new (mono_defaults.object_class, name, MONO_WRAPPER_ALLOC);

int thread_var;

// ... snip ...

EMIT_TLS_ACCESS_VAR (mb, thread_var);

EMIT_TLS_ACCESS_IN_CRITICAL_REGION_ADDR (mb, thread_var);

mono_mb_emit_byte (mb, CEE_LDC_I4_1);

mono_mb_emit_byte (mb, MONO_CUSTOM_PREFIX);

mono_mb_emit_byte (mb, CEE_MONO_ATOMIC_STORE_I4);

mono_mb_emit_i4 (mb, MONO_MEMORY_BARRIER_NONE);

// ... snip: allocation logic ...

EMIT_TLS_ACCESS_IN_CRITICAL_REGION_ADDR (mb, thread_var);

mono_mb_emit_byte (mb, CEE_LDC_I4_0);

mono_mb_emit_byte (mb, MONO_CUSTOM_PREFIX);

mono_mb_emit_byte (mb, CEE_MONO_ATOMIC_STORE_I4);

mono_mb_emit_i4 (mb, MONO_MEMORY_BARRIER_REL);

// ... snip ...

MonoMethod *m = mono_mb_create (mb, csig, 8, info);

mono_mb_free (mb);

return m;

}

With that done, SGen will correctly detect that a managed allocator is

executing no matter how many signal handlers may be nested on the thread.

Checking the in_critical_region variable also happens to be quite a bit

cheaper than looking up JIT info for the managed allocators.

I ran this small program before and after the changes:

using System;

class Program {

public static object o;

static void Main ()

for (var i = 0; i < 100000000; i++)

o = new object ();

}

}

Before:

real 0m0.625s

user 0m0.652s

sys 0m0.032s

After:

real 0m0.883s

user 0m0.948s

sys 0m0.012s

So we’re observing about a 40% slowdown from this change on a microbenchmark

that does nothing but allocate. The slowdown comes from the managed allocators

now having to do two atomic stores, one of which also carries with it a memory

barrier with release semantics.

So on one hand, the slowdown is not great. But on the other hand, there is no

point in being fast if Mono is crashy as a result. To put things in

perspective, this program is still way slower without managed allocators

(MONO_GC_DEBUG=no-managed-allocator):

real 0m7.678s

user 0m8.529s

sys 0m0.024s

Managed allocators are still around 770% faster. The 40% slowdown doesn’t seem

like much when you consider these numbers, especially when it’s for the purpose

of fixing a crash.

More detailed benchmark results from the Xamarin benchmarking infrastructure

can be found

here.

Conclusion

By setting up a critical region in SGen’s managed allocator methods, we’ve

fixed a number of random crashes that would occur when using sample profiling

together with the SGen GC. A roughly 40% slowdown was observed on one

microbenchmark, however, managed allocators are still around 770% faster than

SGen’s native allocation functions, so it’s a small price to pay for a more

reliable Mono.

In the next post, we’ll take a look at an issue that plagued profiler users on

OS X: A crash when sending sampling signals to threads that hadn’t yet finished

basic initialization in libc, leading to broken TLS access. This issue forced

us to rewrite the sampling infrastructure in the runtime.